How can you cultivate curiosity, imaginative and critical thinking to identify challenges that might lead to radically creative breakthroughs?

Problem-finding is a fundamental capacity of highly creative individuals, according to the book Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Innovation1. It shifts the focus from solving given problems to discovering problems that haven’t yet been identified.

‘It is characteristic of scientific life that it is easy when you have a problem to work on. The hard part is finding your problem.’1

—Physicist Freeman Dyson

Some researchers5 find that problem-driven people are more likely to engage in radically creative behaviours that differ substantially from their habitual behaviours. A problem can be seen as a positive challenge that prompts creative thinking, deep curiosity, active learning and a desire to have a powerful impact. Dyson’s observation that we tend to focus on existing problems doesn’t apply only to science but also to other domains of life.

The term knowledge worker was coined by Peter Drucker in his 1959 book The Landmarks of Tomorrow. A knowledge worker is someone in whose work life information holds a central place and who constantly uses their expertise to provide solutions in the workplace.

Knowledge workers—i.e., researchers, data analysts, programmers, economists, etc.—operate in uncertain, complex, ambiguous, and volatile environments. This creates the need to identify and define problems and find creative solutions.

‘In the early stages of my career, I thought in a rather straightforward, engineer-like way that there were problems and then there were solutions to them,’ says Aalto alum Mikko Dufva, who wrote his doctoral thesis on knowledge creation in foresight and now works as a futures studies specialist. ‘In working life, I got closer to the mess of real life and the reality of how many different ways the problem could be defined and how there could be several approaches to solving it. Fortunately, my studies also gave me tools for identifying and changing my own models of thinking.’

Although a knowledge worker’s attention typically goes mainly towards finding creative solutions to existing problems, there’s also a need to discover problems—problems that promise a major shift in societal evolution.

But that doesn’t mean that solving the problems that come our way should be taken lightly. Quite the opposite: solving the problems we encounter is very important. In this sub-chapter, we focus on the abilities that enable us to identify challenges whose solutions promise radical breakthroughs.

Finding and choosing different types of problems

What kind of problems should you choose, and why?

Not all of the problems in everyday work life call for creativity—for example, installing a new piece of furniture is usually a straightforward task. Problems that have a clear start and finish and include instructions are mainly a question of technical skill, not creativity.

But in the complexities of real life, we also face new and ill-defined problems. These are the kinds of problems we need to identify and solve in order to survive and thrive. Ill-defined problems have at least these three features:

- Ambiguity in goals—it’s up to each of us to interpret and decide upon the goals.

- Multiple paths to a solution.

- Multiple possible solutions.11

Problem-finding is considered the first step in creative problem-solving1,11,12. It can start with noticing the immediate challenges and problems others are facing and then combining them into a new, more relevant problem. Or it can be discovering a problem that nobody else has yet envisioned or spoken about.

Whether you tackle existing problems or discover a new challenge, you may want to reflect on your underlying motives for choosing that direction:

- Why did you prioritize that specific problem? How high is the perceived urgency and relevance of the problem? To what extent would solving this problem significantly affect your life, organization or even society at large?

- What’s your emotional engagement with the challenge? Your choice to spend your time solving a problem is fueled by internal or external motivators. These can range from curiosity and genuine interest to concerns about not disappointing others and fears of being seen as incompetent or lazy.

- Do you have enough knowledge and information to solve the problem? If you lack the necessary information, are you willing to learn? Alternatively, do you know someone who can help? This could lead you to gather more knowledge about the issue, solicit feedback and different viewpoints from relevant stakeholders and develop the ability to explain to others why resolving this problem is important.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

A curiosity to discover problems

Let’s explore how we can increase the likelihood of identifying problems in our environment.

Curiosity is the pursuit or recognition of novel, challenging, and uncertain events and a desire to explore them10. It’s considered a facilitator of creativity7,13. Being curious can help with being creative, and being creative also helps encourage curiosity. How does getting curious increase the chance of discovering challenges of radical creativity?

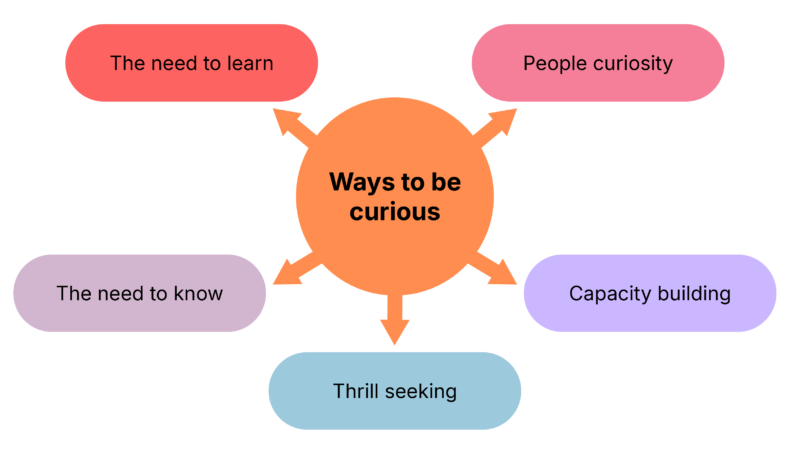

There are many types of curiosity: discovering new areas of specialization (cross-disciplinary) and meeting new acquaintances (people curiosity). Figure 2.3.1. below details a few different ways to be curious. In many ways, the question isn’t how curious a person is but how a person is curious. In other words, what triggers your curiosity?

Perhaps your curiosity is driven by the need to learn and about cross-disciplinary learning, which involves questions such as:

- What are the knowledge areas where you have mastery in?

- What are the knowledge areas that you’d be tempted to learn?

Or the need to know:

- What work-related or other societal topics keep you awake at night?

- When did you work harder to solve a work-related problem that was frustrating you?

Or people-driven curiosity:

- Who are the people you like listening to?

- Who are the people whose conflicts you’d be interested in helping solve?

Or capacity-building curiosity:

- When was the last time you got involved in a new project even though you felt its demands were above your skill level?

- Are you curious to understand what’s behind the anxiety and stress you experience when dealing with new and complex projects?

Or thrill-seeking curiosity:

- What new project would you like to experiment with?

- What’s a new work/learning habit you want to bring into your life?

Reflection

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Researchers Jaussi & Randel8 wanted to understand what drives incremental versus radical creativity. They focused on two drivers: the confidence that you can think and act creatively in a specific moment (creative confidence) and different ways of gathering information.

They looked at how collecting information from within one’s own organization (internal scanning), looking for ideas outside the organization (external scanning) and using personal experiences at work (cross-applying non-work experiences) affect creativity differently. They found that believing in one’s own creative thinking and actions is strongly linked to coming up with radically creative ideas. In addition, they discovered that gathering information from within the organization helps with both incremental and radical creativity, but looking for ideas outside the organization helps with big, groundbreaking ideas.

One takeaway from this research is that you might have better chances of noticing radically creative challenges when you act on new ways to be curious beyond your organization’s boundaries.

Imagination for creative solutions

Imaginative activities are another possible route for becoming aware of challenges for radical creativity.

We can identify two types of imagination6. The first type is socio-emotional imagination — the ability to think about scenarios from multiple social perspectives and imagine consequences for you and other people. When we think of a scenario to realise in the world, the people who would be involved or affected by the outcome influence the content of our imagination.

The second type of imagination is temporal imagination, which is about the ability to engage in mental time travel—past, present, future—and what if thinking. Temporal imagination combines foresight and memory to entertain thoughts of what might have been or what might be.

To apply imagination in everyday life is to engage in mental games of what if questions, identify new experiences that are interesting and asking ‘What if I did that? For whom would I do it?’

Case study

Creative career planning

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Critical thinking in choosing a challenge

How can critical thinking help select challenges that promise a paradigm shift for an organization or community?

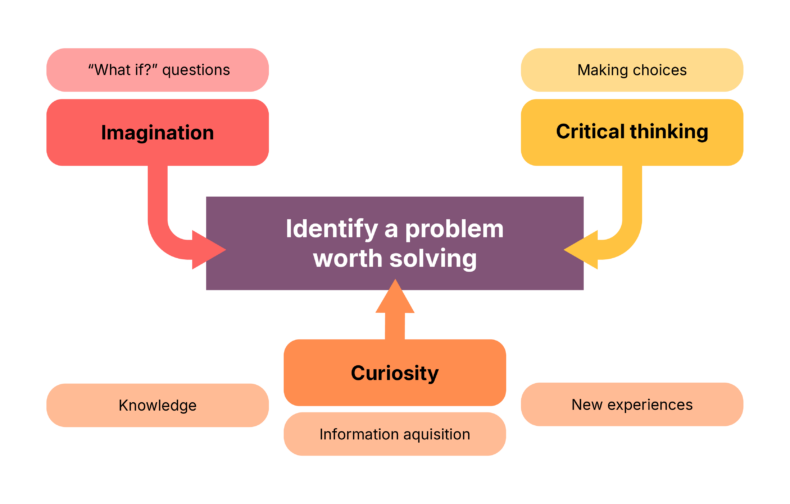

So far, we’ve explored how to use curiosity and imagination to help identify problems worth solving and proactively work on radically creative solutions. We conclude this sub-chapter with critical thinking.

‘Curiosity helps one stop and consider things that may seem insignificant at first,’ said futures studies specialist Mikko Dufva in an interview with Aalto. ‘Critical thinking is particularly important nowadays as well as transformation, especially in identifying and challenging assumptions about the future. Because we often think too narrowly about the future, it is essential to test both our own mindsets and those of others.’

How does critical thinking help us choose radically creative actions?

In the exploration stage of the creative process, before committing to a direction, curiosity and imagination open our eyes to possibilities, and critical thinking enables us to make choices. These three types of thinking skills, pictured in Figure 2.3.2. below, are complementary in creating something totally new4,14. More specifically, they help us identify problems worth solving.

Creative thinking skills enable solution-finding and the creation of radically new services, products, thoughts, concepts, research and art. Critical thinking applies rational thought, with clarity and logic, to evaluate and improve creative ideas and their implementation.

Two questions are at the core of critical thinking2:

- How do I know what I think I know?

- What evidence do I have for what I think I know?

These two questions can be used to reflect on your knowledge about yourself and the world. For instance, when it comes to inquiring into your curiosity and imagination, you can ask:

- How do I know what I think I know about the triggers of my curiosity or imagination?

- What evidence do I have for what I think I know about what makes me curious or imaginative?

- What am I interested in finding out about my curiosity and imagination?

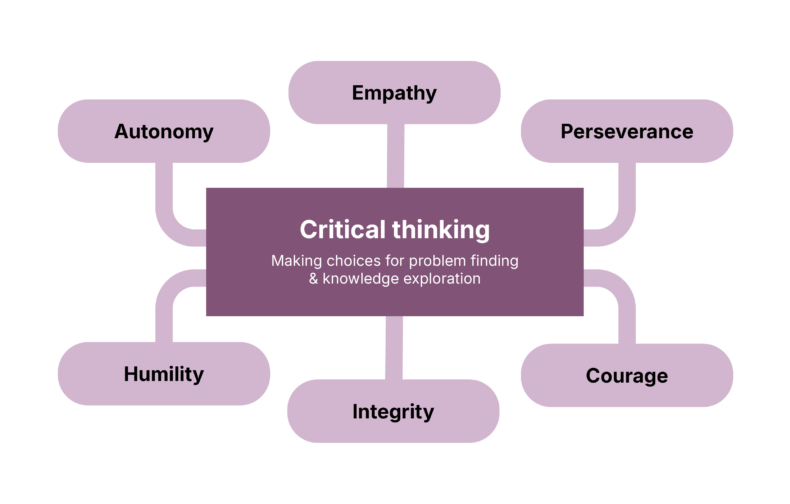

Ultimately, applying critical thinking in the exploration of knowledge for the discovery of radically creative problems depends on personal values, which can be divided into six elements: intellectual humility, integrity, courage, perseverance, empathy, and autonomy, pictured in Figure 2.3.3. below.

Intellectual humility is about admitting that you don’t know as much as you would like to. Knowledge is complex, and it’s impossible to know everything, even when you’re an expert.

Integrity is about honesty, about distinguishing between facts and personal wishes, hopes, intuitions and beliefs.

Courage is about unleashing your imagination and believing in your ideas even when only a handful of people around you validate your actions.

Perseverance is about being determined to work on challenging tasks with complex questions, even in the face of confusion and frustration.

Empathy—cognitive empathy, to be more precise—is about trying to understand others’ perspectives and viewpoints even when you don’t agree with them.

Autonomy is about being able to think for yourself and take responsibility for it.

Real-life activity

Big problem talks

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Problem-finding, knowledge workers, ill-defined problems, prioritization, emotional engagement, knowledge, information, curiosity, creative confidence, imagination, socio-emotional imagination, temporal imagination, critical thinking.

References

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2013). Creativity, The Psychology of Discovery and Invention. HarperPerennial, Modern Classics.

- DiYanni, R. (2015). Critical and creative thinking: a brief guide for teachers. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Drucker, P. (1959). The Landmarks of Tomorrow. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Fatmawati, A., Zubaidah, S., Mahanal, S. & Sutopo. (2019). Critical Thinking, Creative Thinking, and Learning Achievement: How they are related. Journal of Physics: Conference Series.

- Gilson, L. L., & Madjar, N. (2011). Radical and incremental creativity: Antecedents and processes. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 21-28.

- Gotlieb, R. J., Hyde, E., Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Kaufman, S. B. (2019). 34 – Imagination is the seed of creativity. In James C. Kaufman, Robert J. Sternberg (Eds.) The Cambridge handbook of creativity, 2, 709-73.

- Gross, M. E., Zedelius, C. M., Schooler, J. W. (2020). Cultivating an understanding of curiosity as a seed for creativity. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 35, 77-82.

- Jaussi, K.S., & Randel, A. E. (2014). Where to Look? Creative Self-Efficacy, Knowledge Retrieval, and Incremental and Radical Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26:4, 400-410.

- Karwowski, M. (2012). Did curiosity kill the cat? Relationship between trait curiosity, creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 8(4), 547-5.

- Kashdan, T. B., Silvia, P. (2009). Curiosity and interest: The benefits of thriving on novelty and challenge. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 367-374). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reiter-Palmon, R. (2018). Chapter 13 Creative cognition at the individual and team levels: What happens before and after Idea Generation. In Robert J. Sternberg, James C. Kaufman, (Eds), The nature of human creativity, (p. 186-207).

- Runco, M.A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and Themes: Research, Development and Practice. Elsevier Science & Technology.

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M. (2020). A meta‐analysis of the relationship between curiosity and creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(4), 940-947.

- Wechsler, S. M. et al. (2018). Creative and critical thinking: Independent or overlapping components? Thinking skills and creativity, 27, 114-122.

2. Individual

In this chapter, we explore the individual facets of radical creativity that relate to our selves and our creative identity.

2.1 Creative thinking

You’ll explore creative thinking and its neuropsychological basis, along with three key thinking skills. You will also take a personal creativity assessment.

2.2 Inner motivation to create

You’ll delve into two routes to radically creative action: self-determination at work and realizing psychological needs, both of which lead to intrinsic motivation.

2.3 Curiosity and critical thinking

You’ll learn how identifying challenges can drive radically creative outcomes through curiosity, imagination and critical thinking.

2.4 Cultivating a creative identity

You’ll gain insights into four types of creative identities: artistic, abstract ideas, entrepreneurial and empowering.

2.5 Creativity and well-being

You’ll explore three avenues for expressing creativity: tackling challenges in work contexts, experimenting with creative identity, and self-actualization.