What constitutes a paradigm shift? What cycles does a paradigm shift go through?

The concept of a paradigm shift was coined by Thomas Kuhn in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, to describe how scientific knowledge develops and changes over time. A paradigm is defined as the set of assumptions, values and beliefs, concepts, and theories that shape the body of knowledge, which is shared by a group of experts within an existing domain, at a certain point in time. Domains of life such as science, economy, society, technology, and health have all evolved through paradigm shifts, in changes in what we know about the world and how we organize our societies.

Systems thinkers have an expanded understanding of paradigms and paradigm shifting. Donella Meadows (1999) sees paradigms, or mindsets, as places out of which the system – its goals, power structure, rules, its culture – arises. The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions, constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.

One could say that paradigms are harder to change than anything else about a system, but as Meadows argues, there’s nothing necessarily physical or expensive or even slow in the process of paradigm change. Even though societies resist challenges to their paradigm harder than they resist anything else, a single individual paradigm change can happen in a millisecond. All it takes is a new way of seeing.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

How paradigms change

The phases of scientific revolutions

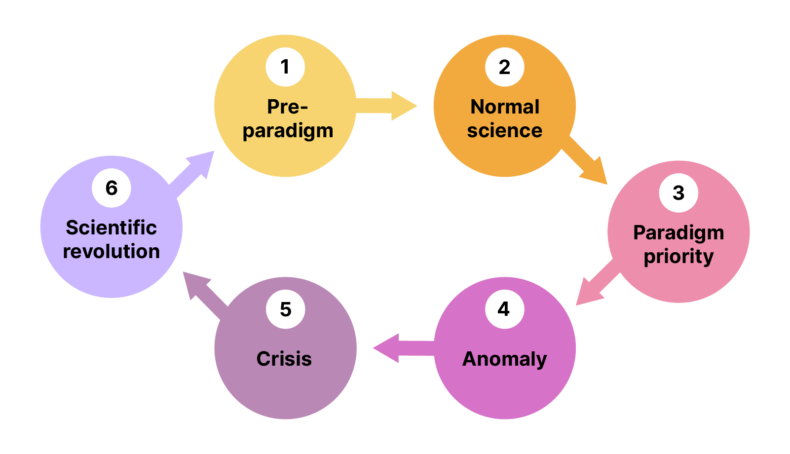

Kuhn (2009) describes the scientific paradigm shifts in six stages. While Kuhn’s research was based on the field of science, a similar type of process can take place in how worldviews and values change radically in society.

In addition, scientific paradigm changes are often a core part of society, and in our era it seems that economics, especially, is influential, for example in how politicians govern national economies.

The six stages of a paradigm change (also depicted in Figure 5.2.1.) are:

- Pre-paradigm

During this phase, the field is characterized by a lack of consensus on fundamental theories, methods, and standards of practice. Scientists in the field may adhere to various competing schools of thought or models to explain phenomena, leading to diverse and sometimes conflicting approaches.

- Normal scienceOne theory or model has proved to be more successful than others in explaining phenomena, solving problems, and predicting outcomes. This success leads most of the scientific community to adopt this framework as the dominant paradigm, which then guides future research and knowledge creation.

- The priority of paradigmsOnce a paradigm isestablished, it becomes the primary lens through which scientists view their field, influencing what questions are asked, how research is conducted, and how results are interpreted. The priority given to an existing paradigm means that scientific research is primarily conducted within its framework, often leading to incremental advancements rather than radical changes.

- Anomaly

Over time, researchers encounter anomalies that cannot be explained by the existing paradigm. These anomalies are initially disregarded or seen as errors, but as they accumulate, they begin to challenge the validity of the current paradigm. In economics, for example, the economic turmoil of the Great Depression of the 1930s presented significant anomalies that the prevailing neoclassical paradigm could not adequately explain. (Cole & Ohanian, 1999). - CrisisWhen anomalies undermine the existing paradigm to a critical point, a crisis occurs, leading to a scientific revolution. This is a period of fundamental change in the scientific community’s view of the field, wherein new theories are proposed to better explain reality.

- Scientific revolutionA paradigm shift happens when the community of experts adopts a new paradigm that better accounts for the anomalies. This new paradigm is not just an extension of the old one but a completely different worldview, which may be incompatible with the previous framework. This change in thinking redefines the strategies and what constitutes a valid idea worth investing time and resources.

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and subsequent developments have prompted re-evaluations of existing economic paradigms, with increasing discussions on the role of financial markets, inequality, and the limitations of traditional models. Another major reform may be on its way as reflected in the dynamics in academic economics, within economic institutions and in civil society (Laybourn-Langton & Jacobs, 2018).

Case study

Amsterdam’s City Doughnut

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Changing societies

Pointing the anomalies

So how do you change whole societies? Meadows says that the key is the anomaly stage, as described by Kuhn above.

‘In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep speaking louder and with assurance from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places public visibility and power’, Meadows writes. She recommends not to waste time with reactionaries but rather connect with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded.

Meadows also says that there is a leverage point even higher than changing a paradigm:

‘That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm is ‘true’, that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, in a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension’ (1999, 19).

Even though there is no certainty of any worldview, paradigms can be useful tools. Radical creatives can choose whatever paradigm that will help to achieve their purpose (Meadows 1999). The humble state of ‘not-knowing’ is a point where radically new things start to take place.

The Iceberg

Everything that we cannot see, but still need to change

Systems change and paradigm shifting require more than what we can see. The iceberg is a visual tool to help us notice and work on the deeper structural blind spots and barriers of systems change. It helps understand the underlying factors of events, and less obvious dynamics and structures that influence human behavior and can cause problems.

Instead of focusing on problems as something that needs to be quickly solved, it is important to approach problems as a symptom of something larger.

Icebergs are infamous for being much bigger underneath the water than what is seen over its surface.

According to Otto Scharmer, we live in a time of massive institutional failure, collectively creating results that nobody wants. The cause of this collective failure is that we are blind to the deeper dimension of transformational change. This “blind spot” exists not only at the institutional level but also in people’s everyday social interactions.

The most efficient factors that provide the deepest impact on system-level change tend to be invisible. So, we really need to reach out and examine these mindsets, assumptions and values that often influence us unconsciously. Questioning society-level issues means questioning things about ourselves. We need to look at ourselves – our inner world – preferably in dialogue with others.

Reflection

Your iceberg

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

From sustainability to regeneration

Shifting the paradigm for businesses – and whole society

Regeneration has become a new buzzword in the field of sustainable innovation. Businesses, entrepreneurs and other actors are increasingly noticing the value of going further than sustainability, and leaning into regeneration. This is seen as a paradigm shift that aims to create a deeper and wider impact and a fundamental shift in business practices.

A key difference between the familiar idea of sustainability and regenerative sustainability, is that the latter is based on a more holistic worldview that sees humans and economies as an intrinsic part of nature. Another key difference is that regenerative approaches start from potential instead of problems because problem solving dictates a future based on past and present problems rather than entire ranges of possibilities. Regeneration is based on what is called ‘living systems thinking’. It emphasizes collective capacity to evolve toward increasing states of health and vitality over time. It focuses on learning how to think like natural systems so that people can shift their role as humans from a species that destabilizes and degrades to a species that revitalizes the living systems that people inhabit. (Gorissen, Bonaldi, Haerens & Rato 2024; see also Gibbons 2020).

According to Gorissen et al. (2024), concrete places are the best starting point for the relearning described above because it is the right scale for most people to think and care about. Place offers a communal ground for people across diverse ideological spectra. Place is what people share in common, and working at the scale of local communities, cities, and bioregions is where individual and collective behavior can make the difference.

Real-life activity

Your doughnut economy

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Paradigm shift, paradigm, pre-paradigm, normal science, priority of paradigms, anomalies, crisis, scientific revolution, mental shortcuts, human independence, economic growth, progress, creative impulses.

References

Allgoewer, E. (2002). Underconsumption theories and Keynesian economics: Interpretations of the Great Depression. Forschungsgemeinschaft für Nationalökonomie an der Universität St. Gallen.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for” mini-c” creativity. Psychology of aesthetics, creativity, and the arts, 1(2), 73.

Bergson, H. (2003). Creative Evolution. Dover Publications Inc.

Bertrand, R. (1997). Principles of Social Reconstruction. Routledge.

Cole, H. L., & Ohanian, L. E. (1999). The Great Depression in the United States from a neoclassical perspective. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 23, 2-24.

Dale, G. (2022). Rule of nature or rule of capital? Physiocracy, ecological economics, and ideology. In Economics and Climate Emergency (pp. 160-177). Routledge.

Dolfsma, W., & Welch, P. J. (2009). Paradigms and novelty in economics: The history of economic thought as a source of enlightenment. American journal of Economics and Sociology, 68(5), 1085-1106.

Florida, R., (2012). The Rise of the Creative Class. Basic Books.

Glasner, D. (2023). Between Walras and Marshall: Menger’s Third Way. Available at SSRN 3964127.

Glăveanu, V. P., & Kaufman, J. C. (2019). A historical perspective. In Kaufman, J.C. & Sternberg, R.J. (Eds), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed, pp 9-26).

Gudeman, S. F. (1980). Physiocracy: a natural economics. American Ethnologist, 7(2), 240-258.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99-127).

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of general psychology, 13(1), 1-12.

Khun, T. S., (2009). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The University of Chicago Press (3rd ed.).

Laybourn-Langton, L., & Jacobs, M. (2018). Paradigm shifts in economic theory and policy. Intereconomics, 53(3), 113-118.

Madjar, N., Greenberg, E., & Chen, Z. (2011). Factors for radical creativity, incremental creativity, and routine, noncreative performance. Journal of applied psychology, 96(4), 730.

Magnusson, L. (2015). The political economy of mercantilism. Routledge.

Mason, J.H., (2003). The Value of Creativity, The Origins and Emergence of a Modern Belief. Routledge.

Pincus, S. (2012). Rethinking mercantilism: political economy, the British empire, and the Atlantic world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The William and Mary Quarterly, 69(1), 3-34.

Rashid, S. (1980). Economists, economic historians and mercantilism. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 28(1), 1-14.

Schumpeter, J. & Swedberg, R. (2021). The Theory of Economic Development. Routledge.

Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (2003). The contributions of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. The Journal of Behavioral Finance, 4(2), 54-58.

5. Impact

In this chapter, we explore how radical creativity impacts our lives, both individually and as a society, by bringing about significant changes for the better.

5.1 Systemic impact

You’ll learn about systemic impact and the key players involved in driving radical creative outcomes.

5.2 Paradigm shifting

You’ll explore how new knowledge shapes policies and societies, including examples of paradigm shifts in economic theories in time.

5.3 Future coming into being

You’ll understand personal and collective transformation as the foundation for creating a sustainable future, reflecting on five inner skills of creativity.

5.4 Changing the world for better

You’ll gain insights into various future scenarios while learning foresight methodologies and how creative practices support transformative futures.

5.5 Novelty and innovation

You’ll examine incremental, disruptive, and radical innovation, understanding the distinctions between radical creativity and innovation. You will also learn how interorganizational approach drives creativity.

Nice! You have completed the activity successfully.

Nice! You have completed the activity successfully.