What does it take to have a passion for your work? What does it take to create?

Being passionate about work typically means having a deep and constant enthusiasm and dedication towards one’s job or career. In this sub-chapter, we discuss what lies behind the enthusiasm to create.

It’s hard not to underestimate the importance of motivation for creative work. There are scholars who think that motivation is more important for creativity than intelligence or talent3. Other researchers say that drive is a crucial characteristic of creative people 5,6,8. In particular, intrinsic motivation—the drive to do something because it’s inherently interesting, enjoyable or challenging—seems to be associated with radical creativity, while extrinsic motivation—some form of reward, such as money or status—can sometimes be part of the motivation for incremental creativity but doesn’t generally drive radical change4.

Strong intrinsic motivation reinforces another crucial characteristics for radical creativity: persistence. It’s important to overcome challenges and setbacks and continue even without immediate rewards or being assured of success. Radically creativity people often have a kind of can-do attitude behind their creativity, a trust that they will be creative and find solutions2.

On the other hand, very ambitious creative goals can actually hinder radical creativity. Researchers think that this is because these goals can lead to too much time being spent monitoring, comparing and assessing actions instead of following the creative process itself. There’s certainly a high element of risk in radical creativity: persistent concentration on inner motivation, without a guarantee of success. But success isn’t the driving force; passion is.2

While intrinsic motivation can’t be directly taught or imposed, it can be nurtured, understood, respected and taken seriously as a driver of radical creativity.

Your podcast guide to the ups and downs of creativity

Oana Velcu-Laitinen, PhD, is one of the main writers of this course. She is a NeuroLeadership coach and trainer focusing on creative thinking to enhance work performance. She works with individuals on their creative paths. In this podcast with Tomi Kauppinen, the head of Aalto Online Learning, she talks about creative identity, with its emotions and battles. The episode is an excellent support and guide for anyone engaging with creativity.

Enjoy the episode. If you cannot see the Spotify player below, you can use this link.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

A story of persistence

What does creative dedication look like?

The Dutch surrealist M. C. Escher is a great example of an artist who was dedicated to his work. In a letter to his son Arthur on November 12, 1955, Escher wrote:

‘I believe that to produce prints the way I do is almost strictly a matter of wanting so terribly much to do it well.

Talent and all that are really for the most part most baloney. Any schoolboy with a little aptitude can perhaps draw better than I; but what he lacks in most cases is that tenacious desire to make it a reality, that obstinate gnashing of teeth and saying, “Although I know it can’t be done, I want to do it anyway”.’

(Escher on Escher, Exploring the Infinite)

For the first 30 years of Escher’s career, his artistic works brought in a modest income. It was only in the last 20 years of his career that he received fame. Escher’s work was triggered by an inner drive to create; it wasn’t about feeling good or talented but about the curiosity and determination to find a satisfying solution to a problem that occupied him. In 1965, he said:

‘I cannot help mocking all our unwavering certainties.

Are you sure that a floor cannot also be a ceiling? Are you absolutely certain that you go up when you walk up a staircase?’

Creating is about finding and following your drive to create. It’s about falling in love with an idea and following through. It’s about taking the risk of doing something that might not succeed or that could turn out to be groundbreaking.

In other words, being a creator means following the flow of your inner drives and finding the problems you enjoy working on so you can be creative out of pure curiosity and despite the risks.

Reflection

Your intrinsic motivation

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Fairness as a drive for creativity

What’s your calling?

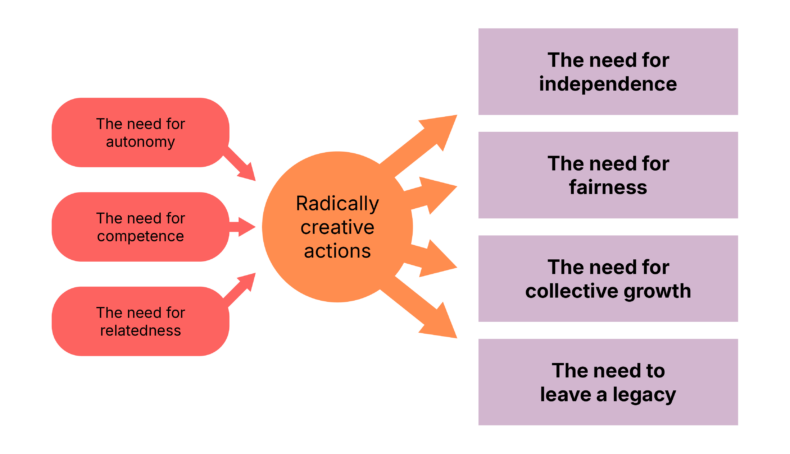

Sometimes radical creativity is driven by a strong psychological need for fairness, collective growth or leaving a legacy10 (see Figure 2.2.1.).

The brain’s reward centres, basal ganglia and the ventral prefrontal cortex are activated not only by material rewards but also by social rewards like fair treatment. For instance, researchers Massi and Luhmann7 found that the brain processes fairness as a pleasurable experience, similar to physical or monetary rewards.

Fairness is a human need that refers to the innate desire for equal and just treatment in social, economic, and interpersonal interactions. This need is deeply rooted in our sense of morality and ethics.

Collective growth is also a strong force of radical creativity. It is grounded in the personal need to belong to a group. This sense of belonging serves as an inner motivation to take initiative and create experiences and actions that uplift the community individually and as a group.

The last type of creative initiative can come from the intention of leaving a legacy for the next generation. Different cultures place varying degrees of importance on the idea of legacy, which can shape how individuals within those cultures perceive and pursue legacy-building activities. Moreover, personal experiences, values, and the desire to have an impact and be remembered can greatly influence one’s creative drive.

Sometimes radical creativity looks like rebellion. Being creative often means thinking differently and unconventionally, which can cast passionate and persistent creative people into the role of a rebel or deviant. Because they’re determined and highly intrinsically motivated, they’re ready to challenge the status quo. They might, for example, seek solutions outside of formal organizations and explore radical behaviours2.

While this kind of creative deviance can take place in any field, from arts to business, we would like to bring attention to a sphere of activity that’s often overlooked when discussing creativity: activism. Activists often work with very limited resources, but they use their persistence and a deep inner motivation to find novel ways to communicate about their cause and drive change2.

According to research, rebellion alone isn’t enough for radically creative output; it should be matched with political skills of navigating communities and organizations in order to gain acceptance and resources. This combination of radical creativity and political skills is important for any creative person with a passion to change the rules of the game, whether in business, arts or activism2.

Case study

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

A work environment that motivates

Sometimes, people don’t recognize what they have a passion for until they try things. How can you discover your dormant passions?

How can we become more deliberate about finding the drive to create? Intrinsic motivation is built on inner subjective experience. An activity that sparks a friend’s passion may not have the same effect on you. Even if you copy what your friend is doing, you might not be equally excited.

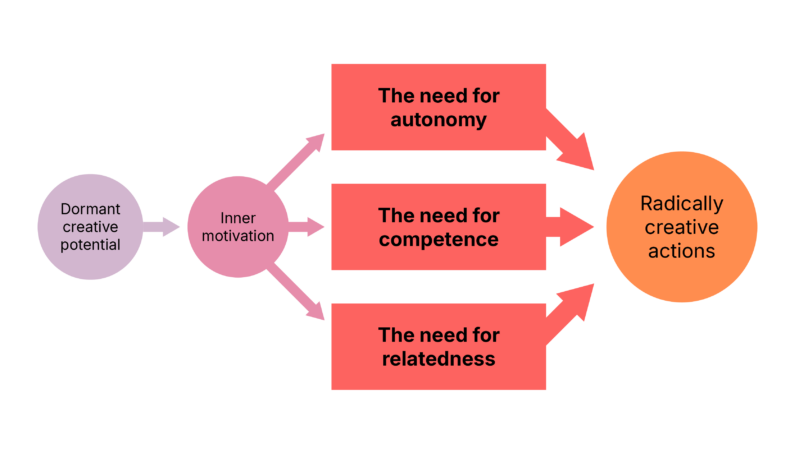

You can nurture inner motivation by looking for social, learning and work environments that accommodate the following sources of motivation: the need for autonomy, the need for competence and the need for relatedness1,9. These needs, pictured in Figure 2.2.2. below, are innate in each of us.

Here, the need for autonomy refers to a need to have a sense of self-determination, choice and ownership over your decisions and behaviours. The need for competence is a need to have a sense of mastery over current skills and confidence about developing new skills — feeling able to achieve your goals. The need for relatedness means a need to feel a sense of connection with others who are involved in what you do — colleagues, teammates, supervisors, clients, etc.

They drive us towards self-determined behaviours, goals and projects, and as such, enable us to pursue radically creative actions.

Figure summary

Three needs to pursue radically creative action

- The need for autonomy

- The need for competence

- The need for relatedness

These needs are tied to our inner motivation.

Let’s take a graphic designer as an example. How might they express their psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness within their role?

They could express their need for autonomy by seeking projects that allow creative freedom. For instance, they might prefer to work on assignments where they have the liberty to choose the design elements and the overall aesthetic, reflecting their personal style and decision-making.

To fulfill their need for competence, the designer might take on challenging projects that require advanced skills or learning new design software. Completing these projects would enhance their sense of mastery and effectiveness in their professional domain.

The need for relatedness could be met by building strong relationships with colleagues and clients. Participating in team projects, collaborating with other departments, or being part of a community of designers which shares ideas and meaningful feedback would help them feel connected and valued within their social and professional circles.

To sum up, people will likely experience intrinsic motivation when they respect their self-determination needs in a specific learning or workplace environment. Then they’ll find it easier to concentrate, persevere and possibly achieve creative outcomes.

Real-life activity

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Creator, drive, intrinsic motivation, inner motivation, persistence, need for autonomy, need for competence, need for relatedness, independence, fairness, collective growth, leaving a legacy.

References

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

- Eloranta, V., Hakanen, E., Shaw, C. (2024). Teaching for paradigm shifts: Supporting the drivers of radical creativity in management education. Educational Research Review 45, 100641.

- Flaherty, A. W. (2018). 2 – Homeostasis and the control of creative drive. In Rex E. Jung, Oshin Vartanian (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the neuroscience of creativity, 19-49.

- Gilson, L.L., Madjar, N. (2011). Radical and incremental creativity: Antecedents and processes. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 21–28.

- Hennessey, B. A. (2015). Creative Behavior, Motivation, Environment and Culture: The Building of a Systems Model. The Journal of Creative Behavior Volume 49, Issue 3 p. 194-210.

- Hennessey, B. A. (2019). 18 Motivation and Creativity. In James C. Kaufman, Robert J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity, 374.

- Massi, B., Luhmann, C.C. (2015). Fairness influences early signatures of reward-related neural processing. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 15, 768–775.

- Ruscio, J., & Amabile, T. M. (1996). How does creativity happen. In N. Colangelo & S. G. Assouline (Eds.), Talent development, Vol. III.

- Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

- Velcu-Laitinen, O. (2022). How to Develop Your Creative Identity at Work. Apress.

2. Individual

In this chapter, we explore the individual facets of radical creativity that relate to our selves and our creative identity.

2.1 Creative thinking

You’ll explore creative thinking and its neuropsychological basis, along with three key thinking skills. You will also take a personal creativity assessment.

2.2 Inner motivation to create

You’ll delve into two routes to radically creative action: self-determination at work and realizing psychological needs, both of which lead to intrinsic motivation.

2.3 Curiosity and critical thinking

You’ll learn how identifying challenges can drive radically creative outcomes through curiosity, imagination and critical thinking.

2.4 Cultivating a creative identity

You’ll gain insights into four types of creative identities: artistic, abstract ideas, entrepreneurial and empowering.

2.5 Creativity and well-being

You’ll explore three avenues for expressing creativity: tackling challenges in work contexts, experimenting with creative identity, and self-actualization.