How can we use futures thinking for change? What should we learn to create change?

While the future cannot be precisely predicted, it’s worth trying to anticipate it. There isn’t just one right future. There are a range of possible futures, and we can actively shape the future through our decisions and actions today. In this sub-chapter, we talk about how to create the future.

Futures thinking is a creative and exploratory process that sees many possible trajectories and acknowledges uncertainty as a key condition. Futures thinking, also known as foresight, is a discipline and profession in its own right. Experts create useful theories and frameworks for making wiser decisions through understanding the long-term issues and challenges shaping the future development of a certain issue or area3,12. We’ll now turn our attention towards some essential insights coming from the work of such futurists.

The scale of future thinking

From your grandchildren to global issues

When you hear the word ‘future’, what kind of topics or issues come to your mind?

Futures thinking is centered around imagining how a current theme or issue that matters to you will develop in the future. You can’t imagine a future about a vague topic. But you can engage in future thinking about your professional life, your grandchildren’s living environment and livelihood opportunities, the changes in society in the next fifty years or the planet’s carrying capacity and vitality in the next few hundred years.

There are different foci and time horizons of future thinking—from the micro level of our individual experiences to the macro level of our societal experiences and finally to the grand level of human civilization—based on which we can exercise our ability to envision and forecast alternative scenarios.

Another way to think about future and create scenarios about it is to look at the matter from the perspective of five different kind of futures12:

- The potential future refers to all the future events that are about to unfold, including both the ones we can imagine as well as those we cannot.

- The possible future perspective includes all sorts of future scenarios that we could possibly imagine by breaking the assumptions of the existing knowledge.

- In contrast, plausible futures reflect the events that could happen according to our general knowledge of how things work.

- The probable future imagines alternative future scenarios that are likely to happen based on the existing trend.

- Preferable futures are about scenarios that we would like to happen.

So, the potential future perspective refers to everything that could happen, whereas the possible, plausible and probable future perspectives strive to forecast future in relation to existing knowledge. The preferable futures are subjective, and emerge from our feelings and values.

Future envisioning

A three step method for envisioning the future

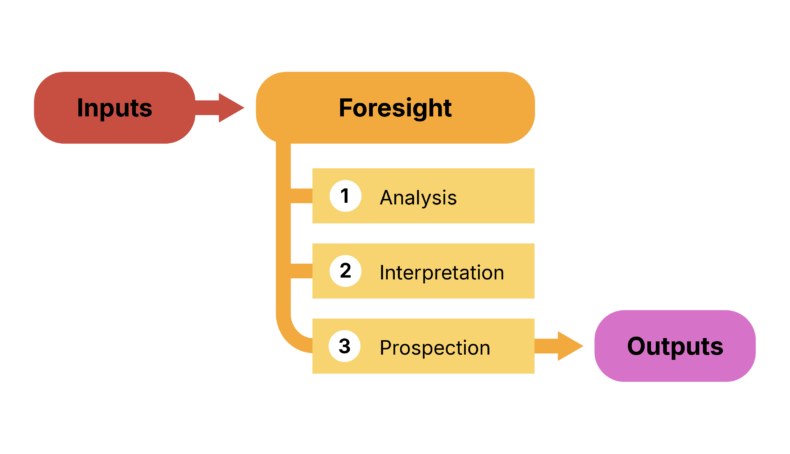

Three steps in creating future scenarios: input, foresight work, and output (see figure 5.4.1).12

The input stage could be called research. It refers to scanning the environment where the topic of interest takes place and collecting information about random events, trends, key actors and their actions, and key relationships between key actors. The data is then used as a basis for forming key questions that open the mind to future visions.

The foresight stage consists of three steps: analysis, interpretation and prospection.

For analysis, there are different methodological tools, such as the futures wheel. Developed by futurist Jerome Glenn in the 1970s, the futures wheel is used for exploring and mapping out the potential direct and indirect consequences of a specific trend or event5. Other methodologies include the cross-impact matrix and trend analysis, which have a similar aim of analysing and understanding how different actors and events might interact with and influence each other. Useful methods are presented on the website of United Nations innovation lab UN Global Pulse, for example.

Next comes the interpretation of the identified consequences and connections of the events. What is happening beyond the surface of the identified patterns? The aim is to understand what the causes of the observed trends and events might be.

At the prospection stage, a future scenario is generated based on the future type you are interested in—potential, possible, plausible, probable or preferable.

Last comes the output stage, where the scenarios generated are taken into consideration in making strategic decisions and taking actions towards actually creating the future.

All in all, these three stages are meant to open the mind to the alternative visions which weren’t even considered at the outset. This framework can also increase awareness of the drivers of change for enabling a preferred future.

Figure summary

Voros’ three steps for formulating alternative scenarios

- Input. First we collect information about the topic of foresight.

- Foresight. After collecting the information, it is analyzed and interpreted, and a future scenario is generated accordingly.

- Output. As the final step, the scenario is used to produce decisions and actions.

All in all, these three stages are meant to open one’s mind to the alternative visions related to the phenomenon of interest, which were not even considered at the outset. Also, this framework can increase awareness of drivers of change for enabling a preferred future.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

High-tech and high spirit transformation

What is the role of arts?

Societal transformation envisions a future where current behaviours, beliefs, norms and organizational forms transform into new ones. These new forms are distinct from a mere return to older or traditional models. In general, futures studies discusses two primary categories of societal transformation: ‘high-tech’, which focuses on technological breakthroughs, and ‘high spirit’, which centers on consciousness transformations13.

The role of technology in societal transformation is enormous, and often unplanned and unforeseen. The automobile, for example, led to increased suburbanization, to the detriment of many city centers, and to the proliferation of malls. The digital revolution has fundamentally transformed the whole world and is still continuing. It’s important to understand that the outcomes of new technologies are not a law of nature but depend on the paradigms of thinking, values and beliefs in societies. By transforming these, we can also influence the effects of new technology.

Arts and creative practices can stimulate a high spirit transformation. Creative practices can be performed by both professionals and volunteers who use their personal and collective craft skills and creativity to innovate or reinterpret aspects of the world. This can be done using many creative methods from writing, art and theatre to design and participatory community development.

Creative practices stimulate transformation by creating emotional experiences that could ‘change us by giving a foretaste of what radical respect for life might be like’7. They can help individuals to develop new meanings about transformational futures via embodiment, learning and imagining.

Embodiment refers to the the use of the body to experience and comprehend the world. Embodiment enables access to diverse ways of knowing, facilitating a deeper connection with various perspectives that are often overlooked in approaches that center around rationality. Embodiment connects to metaphors and meaning, allowing for a physical engagement with ideas and theories. For example, the organizers of the creative practice Invocation for Hope invited people into a burnt but secretly alive indoor woodland. This immersion evoked many reflections on new embodied experiences among visitors, who described mixed feelings of desolation and aliveness.9

Embodiment fosters changes in emotional energy and social interactions, which can lead to new values and social relationships that are essential for transformations.

Learning has a profound impact when it involves changes in basic assumptions, worldviews and knowledge. Creative practices play a significant role in facilitating this. One need only think of influential movies, books or songs.

Individual learning requires deep evaluation and reflection, which can lead to personal transformation. Social learning is also essential; it’s when individuals collectively gain insights through communication, observation and problem-solving. This relational and collective learning fosters a shared critical consciousness that recognizes societal issues as structural. Ultimately, both individual and collective learning processes are crucial for shaping actions toward sustainability transformations.

Imagining refers to imagined futures, presents and pasts. Art and creative practices expose people to new ways of being or doing that can expand their imaginative capacity. The frequent communication of visions and narratives of the future can gain widespread attraction, garnering support and resources. These visions may evolve into imaginaries, which are images of the future that are backed by different organizations and repeatedly presented to the public. Such imaginaries open up new possibilities for change.

As imaginaries gain institutional support and public recognition, they become deeply intertwined with institutional change, shifts in public perception and systemic transformations.

The video below shows how the artist and designer Julia Lohmann works and thinks. If you can’t see the video embedded below, you can watch it here.

Reflection

Art in your life

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

The Three Horizons framework

Negotiating the future

There is tension between making incremental changes—improving what’s already working—and the need for radical transformation. In any discussion about changing the future, there are usually three perspectives or voices that emerge. These three voices often talk past each other, but each is needed to create meaningful change. The ‘Three Horizons’ framework, developed by futurist Bill Sharpe and his colleagues, is a helpful tool for exploring future-oriented innovation and making radical and wise change actually happen:

Horizon 1

The dominant way things are done today that shows signs of strain and a lack of fit with the future.

Horizon 3

Our visions of how we want things to be radically different in the future.

Horizon 2

The innovations we can create right now that will help realise the desired future.

The framework evaluates change by bringing these three horizons together in a way that recognizes the value of each perspective and gives different stakeholders a shared language for exploration. Where are we right now? Where do we want to be in the future? How do we get there?

In the video below, Kate Raworth, the economist behind the well-known concept of a sustainable Doughnut Economics, explains how the three horizons model can be used. If the embedded video doesn’t work, you can watch it here.

Case study

Uber and Ride Austin

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Planetary work

What is the role of humans on the planet?

Due to the impact of increasingly consumerist societies, primarily in the Global North, the Earth is undergoing profound and probably irreversible changes in its systems, environment, processes and biodiversity.

How can we, as creators and decision-makers, change the direction of development? An important viewpoint for changing the world comes from planetary thinking8. Human-induced climate change, the depletion of natural resources and declining biodiversity call for radical creativity from a worldview that sees no separation between the planet and its citizens.

Planetary imagination and inclusion can be stimulated by broadening our perception spatially, temporally and ethically. We are not just residents of a city or a nation. We live on a finite planet with all the other people and life forms. There is also a chain of connections between generations: those who lived before us laid the foundations for our well-being, and our choices influence the lives of those to come. When our ‘sphere of care’ and ‘sense of belonging’ broadens towards planetary responsibility, new questions open up that help create new ways to thrive on our unique planet. For example, what might a desirable future look like from the perspective of marine corals, Congolese miners, Pacific Islanders or unborn children?8

Effective change work connects humans with ‘more-than-human’ realities. A holistic worldview is typical of Indigenous traditions, which can provide enriching perspectives for learning and innovation. For example, Indigenous wisdom says that ‘there is only one water’, implicitly recognizing the connectedness of the global water cycle. Connections between human and ‘more-than-human’ realities can be identified in real-life everyday acts: when I breathe, I breathe in the oxygen that plants produce. When I eat, I consume part of the world into myself, becoming a part of the living and non-living world—its plants, water, light and soil.8

Watch the talk by Arto O. Salonen, professor at University of Eastern Finland, on planetary thinking and education. The video has English subtitles if you need them. If the embedded video doesn’t work, you can watch it here.

Real-life activity

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Future, future thinking, potential future, possible future, plausible future, probable future, preferable future, input, foresight, output, analysis, interpretation, prospection, futures wheel, high-tech, high spirit, embodiment, learning, imagining.

References

- Beaty, R.E., Benedek, M., Wilkins, R.W., Jauk, E., Fink, A., Silvia, P.J., Hodges, D.A., Koschutnig, K., and Neubauer, A.C. (2014). Creativity and the default network: A functional connectivity analysis of the creative brain at rest. Neuropsychologia, 64, 92-98.

- Carson, S. (2012). Your Creative Brain: Seven Steps to Maximize Imagination, Productivity, and Innovation in Your Life. Jossey-Bass.

- Dator, J. (2019). What futures studies is, and is not. Jim Dator: A Noticer in Time: Selected work, 1967-2018, 3-5.

- Furtherfield. 2022. The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025. https://creatures-eu.org/productions/treaty/

- Glenn, J. C. (2009). The futures wheel. Futures research methodology—version 3, 1-19.

- Herbet, G., & Duffau, H. (2020). Revisiting the functional anatomy of the human brain: toward a meta-networking theory of cerebral functions. Physiological Reviews, 100(3), 1181-1228.

- Light, A. (2023). In dialogue with the more-than-human: Affective prefiguration in encounters with others. interactions, 30(4), 24-27.

- Salonen & Siirilä 2019: Transformative Pedagogies for Sustainable Development. in W Leal Filho (ed.), Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. Springer, Cham, pp. 1-7. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-63951-2_369-1 )

- Superflux. 2021. Invocation for hope. Superflux, London, UK. https://creatures-eu.org/productions/invocation/

- Toivonen, S., Rashidfarokhi, A., & Kyrö, R. (2021). Empowering upcoming city developers with futures literacy. Futures, 129, 102734.

- Vervoort, J., Smeenk, T., Zamuruieva, I., Reichelt, L. L., van Veldhoven, M., Rutting, L., … & Mangnus, A. C. (2024). 9 Dimensions for evaluating how art and creative practice stimulate societal transformations. Ecology and Society, 29(1), 29.

- Voros, J. (2003). A generic foresight process framework. foresight, 5(3), 10-21.

- Voros, J. (2017). Big History and anticipation: Using Big History as a framework for global foresight. Handbook of anticipation: Theoretical and applied aspects of the use of future in decision making, 1-40.

5. Impact

In this chapter, we explore how radical creativity impacts our lives, both individually and as a society, by bringing about significant changes for the better.

5.1 Systemic impact

You’ll learn about systemic impact and the key players involved in driving radically creative outcomes.

5.2 Paradigm shifting

You’ll explore how new assumptions and mindsets shape policies and societies, including examples of paradigm shifts in economic theories over time.

5.3 Future coming into being

You’ll understand personal and collective transformation as the foundation for creating a sustainable future, reflecting inner skills of creativity.

5.4 Changing the world for better

You’ll gain insights into various future scenarios while learning foresight methodologies and how creative practices support transformative futures.

5.5 Novelty and innovation

You’ll examine incremental, disruptive and radical innovation, understanding the distinctions between radical creativity and innovation. You’ll also learn how an interorganizational approach drives creativity.