What is collaboration and why is it important? How is creativity promoted through diverse, multidisciplinary collaboration?

Janne Halme, a physics lecturer at Aalto University, cites lab managers at multidisciplinary labs as an example of how the university’s environment supports collaborative creativity. ‘The managers at multidisciplinary labs like BioGarage and CHEMARTS are cornerstones who many people interact with. They know a lot about what’s going on in research throughout the university,’ he says. ‘So someone who joins those labs with a project idea can get recommendations from the lab manager about who they should meet, perhaps to develop that idea.’

To Halme, these people are a creative force that can create new collaborations within the community. Collaboration starts with someone taking initiative and involving other experts in discussions. It means working together with people who have different skills and perspectives to achieve a shared goal.

People engaged in collaborative creativity have a common goal of generating, implementing and promoting creative ideas, processes, products and services. This form of creativity involves people with diverse roles and competencies consciously participating in projects that have greater risk and uncertainty9,10. Similarly, the concept of distributed creativity understands creative thinking as a process that occurs between people, or people and objects, and across time6,15. From this perspective, all forms of creativity are essentially distributed or collaborative, even if a person seems to be working alone5,13.

Collaboration connects people, ideas and resources which normally wouldn’t interact (Cardoso de Sousa, et al, 2012). You can collaborate with people who are working in the same team or with people in different departments or even outside the organization, such as clients or contractors. Collaboration can happen across different disciplines and fields.

Collaboration is valuable in both practical and emotional terms. For instance, social cues which signal an invitation to work with others can boost intrinsic motivation even when people work on tasks alone3. Working together doesn’t necessarily mean that you work with another person on a specific problem at the same time or in the same place. It’s more about the feeling of joint engagement with friendly people as you perform your individual tasks. Symbolic social cues of joint engagement can turn work into play, making people more interested in challenging tasks, so they persevere longer, enjoy their work more and become more absorbed.4

Take a book as an example. The people mentioned in the acknowledgments, like the agent, editor, marketing director, partner, etc., are collaborators who helped the author complete the book. Collaborative creativity encompasses a series of social interactions that allow creative ideas to evolve and spread from individual creators or groups to the organization, then to the broader ecosystem and ultimately to other people in society.

In summary, even if you’re the sole creator of a project, it helps to be proactive in attracting people to help with knowledge sharing, access to resources and emotional support.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Open collaboration

Let’s look at some examples of open collaboration for generating ideas or refining solutions.

In an open collaboration, you invite people from inside or outside the organization to generate ideas. This can happen before you identify a creative idea or later in the creative process, when you need support to develop your idea into a finished initiative, process or product. Open collaboration is characterized by having few barriers to entry, allowing anyone interested to contribute and freely share resources, data and ideas. Contributions are valued based on their quality rather than the contributor’s status and are sometimes compensated financially.

For instance, crowdsourcing can be a form of open collaboration that can enable other people to support a project7. Although the term crowdsourcing was only coined in 20068, the technique has existed for much longer. The Toyota logo competition is a good example. In 1936, Toyota decided to separate its automotive division and create a new brand identity for it. They launched a public competition to design the logo for the new automotive company. The contest attracted over 27,000 entries, showcasing a wide range of ideas and creativity from the public. The winning entry was a design that stylized the letters of “Toyota” in a way that was both visually appealing and easily recognizable.

A more recent example of crowdsourcing is Lego’s Create and Share website, where people can share ideas, and those that receive 10,000 supporters get invited to collaborate with Lego designers to create them.

Reflection

Who to collaborate with?

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Closed collaboration

What types of outcomes can closed collaboration produce?

Closed collaboration is most useful when you’re working on a start-up or an innovative product to commercialize. Closed collaborative groups are much smaller, and they involve more frequent and closer interaction between members.

Co-design is an example of closed collaboration. It’s based on the idea that the user is an important partner in the process of creating a new product14. Organizing co-design workshops requires intimate and intensive interactions between participants, usually a relatively small, well-defined group of stakeholders working together closely throughout the design process. In co-design, stakeholders, such as users, designers and other relevant parties, are deeply involved in every step of the design journey, from identifying problems to generating solutions and refining outcomes.

Researchers Botero & Hyysalo2 address the need to develop methods that support ongoing and evolving co-design efforts, especially with groups that might not have a lot of resources, design knowledge or technical skills, such as the elderly. They focus on how to sustain engagement in co-design processes within everyday life, emphasizing the gradual evolution of design practices that adapt to the needs and contributions of older adults. The study highlights the importance of continuous involvement and iterative learning to make technology more accessible and useful for aging populations.

The practice of co-design happens not only in product design but also in educational settings and elsewhere12. Projects might last different lengths of time and go through various stages. The way users and stakeholders contribute can also differ.

Overall, there are three main ideas behind co-design:

- It emphasizes the importance of valuing people and giving them opportunities to contribute. This not only empowers them but also leverages their unique experiences and expertise.

- It promotes the idea that working together generates a richer exchange of ideas and leads to shared discovery and learning.

- It focuses on imagining possibilities and asking ‘what if’ questions. Rather than just understanding a situation, co-design aims to explore new ideas, identify issues and find opportunities for improvement.

Any creative individual who has an idea, ideal, concept, prototype or product to test can follow the principles of co-design to gather participants’ feedback, reactions and preferences14.

An important aspect of any form of closed collaboration is to choose the right people to work with. Once you know what you want to achieve, you need to identify the people who are best suited to contribute. It’s not only about who has the most relevant expertise, experience and skills but also about who is open-minded, able to communicate empathically and good at challenging assumptions.

Figure summary

Forms of collaborative creativity

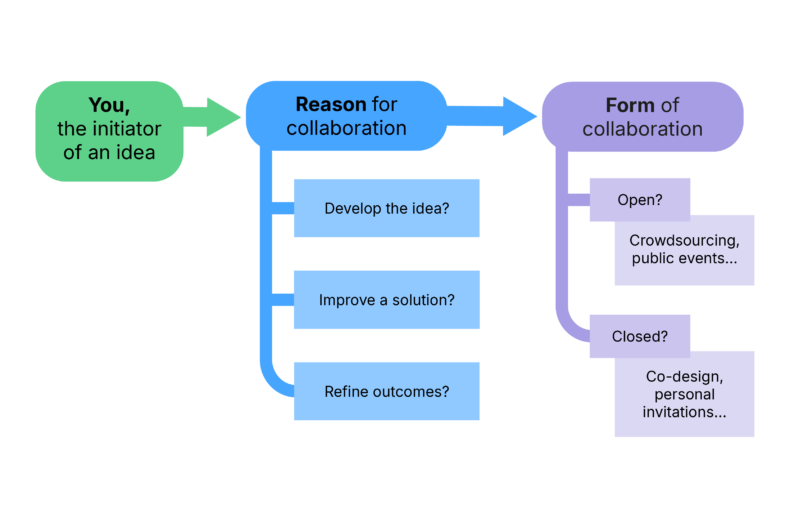

Collaborative creativity has many forms. You, the initiator of the idea, choose what form your collaboration takes. It is important to also consider the reason for the collaboration when making this choice.

Reasons for collaboration:

- Developing an idea.

- Improving a solution.

- Refining outcomes.

Forms of collaboration :

- Open collaboration, like crowdsourcing and public events.

- Closed collaboration, like co-design and personally inviting people to collaborate.

To sum up, as you can see from Figure 4.2.1. above, when you have a radically creative idea, you can choose between open and closed forms of collaboration or a mixture of the two. Be mindful though, of why you want to collaborate and who you ask to contribute so you can choose an approach that’s the best match for your situation and goals.

Case study

Creating a full-scale cardboard hospital for prototyping. Watch the video.

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Creative collaboration

In this last section, we turn our attention towards another type of collaboration, very close to collaborative creativity: creative collaboration.

So far, we’ve discussed collaborative creativity, which is when someone mobilizes others with complementary skills towards the implementation of an idea. In creative collaboration, the creative idea spontaneously emerges during discussions in a diverse team or multidisciplinary group.

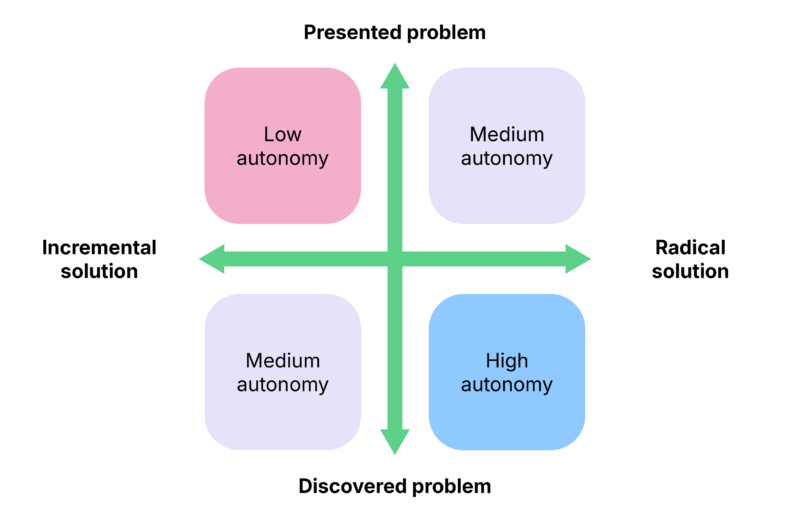

There are different types of ideas that emerge in creative collaboration. Presented problems result in incremental solutions that are usually found in organizations, where groups are formed by management and work within strict limits. Their creativity is somewhat limited by the organization’s rules and expectations.16

Discovered problems will result in ideas for radical solutions, and they’re more common among groups where members are friends. Collaborations among friends provide a lot of freedom to explore and create something completely new. Indeed, as you can see from Figure 4.2. below, working on discovered problems often features a higher level of autonomy than working on presented problems. Researcher Sonnenburg suggested that radically creative outcomes need creative collaboration among people who feel comfortable enough with each other to behave creatively and choose problems that are self-initiated.16

Collaborative creativity and creative collaboration may seem synonymous, but they’re not1,16. In this sub-chapter, we describe them as two distinct concepts that refer to different ways in which creativity happens in social interactions and leads to creative and innovative outcomes.

The main difference between the two forms of collaboration is the role of individuals. At the outset of a creative collaboration, no one comes up with a creative idea and assembles a group. Nobody owns the idea. The group members have equal status, irrespective of their expertise and seniority, and the creative ideas emerge during the interactions.

By contrast, in collaborative creativity, people are invited to form a group that aims to find together solutions to a pre-defined problem within an organizational or learning setting.

Real-life activity

Design a public park

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Collaboration, collaborative creativity, distributed creativity, open collaboration, crowdsourcing, closed collaboration, co-design, creative collaboration, presented problems, discovered problems.

References

- Barrett, M. S., Creech, A., & Zhukov, K. (2021). Creative collaboration and collaborative creativity: a systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 713445.

- Botero, A., & Hyysalo, S. (2013). Ageing together: Steps towards evolutionary co-design in everyday practices. CoDesign, 9(1), 37-54.

- Cardoso de Sousa, F., Pellissier, R., & Monteiro, I. P. (2012). Creativity, innovation and collaborative organizations. The International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 5(1), 26-64.

- Carr, P. B., & Walton, G. M. (2014). Cues of working together fuel intrinsic motivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 169-184.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity (pp. 47-61). Springer Netherlands.

- Glăveanu, V.P. (2014). Distributed Creativity: What Is It?. In: Distributed Creativity. Springer Briefs in Psychology. Springer, Cham. pp. 1-13.

- Hossain, M., & Kauranen, I. (2015). Crowdsourcing: a comprehensive literature review. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 8(1), 2-22.

- Howe, J. (2006). The Rise of Crowdsourcing. Wired.com.

- Huang, M. H., Dong, H. R., & Chen, D. Z. (2012). Globalization of collaborative creativity through cross-border patent activities. Journal of Informetrics, 6(2), 226-236.

- Jeppesen, L. B., & Lakhani, K. R. (2010). Marginality and problem-solving effectiveness in broadcast search. Organization science, 21(5), 1016-1033.

- Kohtala, C. (2017). Making “Making” critical: How sustainability is constituted in fab lab ideology. The Design Journal, 20(3), 375-394.

- Mattelmäki, T., & Visser, F. S. (2011). Lost in Co-X-Interpretations of Co-design and Co-creation. In Proceedings of IASDR’11, 4th World Conference on Design Research, Delft University,. International Association of Societies of Design Research (IASDR).

- Moran, S., John-Steiner, V., & Sawyer, R. (2003). Creativity in the making. Creativity and development, 61-90.

- Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-design, 4(1), 5-18.

- Sawyer, R. K., & DeZutter, S. (2009). Distributed creativity: How collective creations emerge from collaboration. Psychology of aesthetics, creativity, and the arts, 3(2), 81.

- Sonnenburg, S. (2004). Creativity in communication: A theoretical framework for collaborative product creation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 13(4), 254-262.