What does innovation mean?

The term innovation in the sense we use it today—introducing something new or making changes to something established by the introduction of new elements or forms—is often attributed to the economist Joseph Schumpeter. He used the term extensively in his writings on economics during the early 20th century, particularly focusing on how innovation drives economic development and business cycles.

In fact, Joseph Schumpeter did not coin the term innovation. The word is derived from the Latin innovatus, which means ‘to renew’ or ‘to change’ and has been in use since the 15th century, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. The earliest attested use of ‘innovation’ in the Oxford English Dictionary is from 1548. However, Joseph Schumpeter popularized the term in his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, describing the process by which new products and technologies replace old ones, a concept he termed ‘creative destruction’:

‘The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.’12

His work significantly influenced how we understand the role of innovation in economic growth and industrial transformation.

According to management consultant and educator Peter Drucker4, innovative business ideas come from analyzing areas of opportunity. Four areas of opportunity can be observed within a specific company or industry: unexpected events, incongruities, process needs and changes in the industry. Three areas of opportunity exist within the social and intellectual environments: demographic changes, changes in perception and new knowledge.

Once you notice an opportunity, you’ll need to use your creative thinking and expertise to arrive at an innovative solution. Different types of innovations require different strategic responses from the organizations developing them and change people’s lives in different ways.

Reflection

Making lives better

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Types of innovation

What are three types of innovation?

Incremental innovation makes products better in the eyes of existing customers. For instance, each new smartphone model typically offers slight enhancements over its predecessors. These improvements enable firms to sell more products to their most valuable customers.

By contrast, small companies with fewer resources can successfully challenge established companies, known as incumbent businesses, through disruptive innovation. The disruptors target overlooked segments and position themselves by delivering a novel offering, usually with better functionality or a lower price, and then gradually move upmarket, eventually displacing the incumbents.

There is also a third type of innovation: radical innovation.

To maintain their leading position and sustain their competitive advantage, organizations also need to focus on developing radical innovations and new businesses. This strategy ensures that they can create and capture entirely new markets in the future. For this reason, organizations are increasingly prioritizing the development of cultures that encourage and support innovative behavior. This approach aims to make employees so accustomed to change and innovation that they are not just participants but active creators9.

Whereas incremental innovation—e.g. enhanced camera resolution—helps firms to stay competitive in the short-term, radical innovation focuses on long-term impact and may involve displacing current products, altering the relationship between customers and suppliers or creating completely new product categories. According to systematic review of 40 years of innovation research5, radical innovations are related to topics such as organizational culture and capabilities, social and human capital and project management. They completely transform the way firms engage with the marketplace, and they require completely new technical skills and organizational competencies.

The literature on radical innovation is therefore focused on people. Imagination and the ability to envision the future of technology are important to generate the novel ideas required for radical innovation.

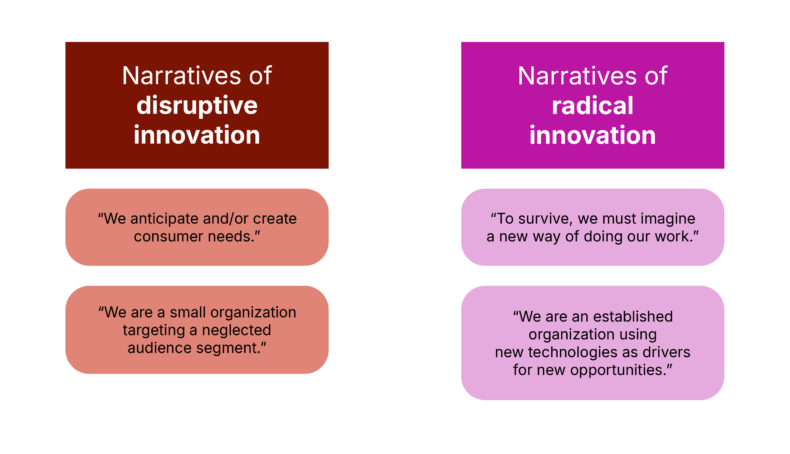

Companies that are interested in radical innovation focus on having the right people to generate breakthrough ideas complementary to their core business. Radical innovation is perceived as a protection against disruptive innovations by market entrants. For small companies that engage in disruptive innovation, the key to growth is in foreseeing customer needs and offering a product based on new technology and innovative business models. Figure 5.5.1. shows examples of the kind of narratives companies might have regarding the disruptive and radical types of innovation.

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

How does radical creativity differ from radical innovation?

Differences in thinking, process and outcome

Radical innovation and radical creativity have a lot in common, but they are distinct concepts that have been developed within different disciplines, psychology and economics, with different assumptions, principles and goals.

For example, professor Andrea Botero Cabrera explains that ‘the two concepts come with a different knowledge and a different history. Creativity is rooted more in disciplines of psychology and human cognition. Nowadays creativity is also understood as a relational quality. Innovation comes from another discipline, that involves inventions and technology. Because of the background, the interest here is less in inner lives and sensibilities and emotions but more in how things work.’

When we define them as a type of thinking, a process or an outcome, the differences can be clarified:

- Radically creative thinking originates from the creative brain. It manifests through the observation of ideas that are fundamentally new and different from existing paradigms and that others may ignore or not notice. It’s the type of thinking that enables some creative individuals to look at a particular challenge or problem from a groundbreaking perspective.

- Innovative thinking is also underlined by mechanisms of creative thinking, including creative imagination, inspiration and intuition. However, its main concern is the practical application of a creative idea to create value for an individual, company or business eco-system or in society. Innovative thinking can also be incremental and radical. In both cases, innovative thinking is reflected in work behaviors and knowledge.

- In radically creative processes, when an individual or a group get an intuition that an experiment can be done, they will engage in creative behaviors that are different from anything they’ve done before. They will accept higher levels of risk, anxiety and discomfort as their behaviors not only challenge existing norms of social interaction but also take them out of their comfort zone.

- Innovation processes are experiments with a product prototype or a new business model and often follow from noticing opportunities in societal or user needs or market gaps. While also risky, the individual and collective efforts in innovation projects are often more managed and mitigated, especially in an organization where there are established structures, leadership and culture for innovation. In innovation environments, leaders usually set a direction by identifying the challenges that need innovative solutions.

- Radical creativity as an outcome reinvents existing organizational cultures, systems, theories or practices. The outcomes can vary from engineering, social, technological, scientific and business innovations to changes in social norms and lifestyles.

- Innovation as an outcome is about a valuable and useful impact through the creation of a tangible new product, business model, work process, etc. The success of an innovation in business is measured in Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) reflecting its ability to solve practical problems related to market needs10,11.

In short, innovations and radical creativity are closely linked. Innovations need creativity; radical innovations need radical creativity. But radical creativity is a concept coming from psychology, referring to new thinking, processes and outcomes that can happen in all areas, fields and disciplines. It may or may not involve commercial activities.

Radical creativity is more about changing perspective to achieve breakthroughs and fundamental changes. Innovation is instead focused on practical application and the successful implementation of new ideas, with the goal of creating new value.

Case study

Accessible MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) solutions for stroke patients

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Give us feedback!

We’d love to hear your feedback on the course! You can share your thoughts anytime during your journey. The feedback link is at the top left-hand side of the page. We hope you can take a moment to let us know what you think!

Great that you’re here!

Give feedbackTo conclude, in this subchapter, we looked at what innovation is and at the similarities and differences between radical creativity and innovation. We covered the following key ideas:

- Joseph Schumpeter, a key figure in the study of economics in the 20th century, introduced the idea of innovation in the field of economics under the term ‘creative destruction’, which was described as the creation of new consumers goods, new methods of production, new markets and new structures in industrial organizations.

- In 1997, economist, professor and author Clayton Christensen proposed the theory of disruptive innovation, describing a type of innovation that causes shifts in an existing industry through the creation of new markets or new consumer needs. Studies of innovation recognize two other types, incremental and radical. Incremental innovation is about improving the quality of an existing product for short-term profit. Radical innovations are about an organization’s ability to reinvent its culture and structures so that the employees can have space for innovative behaviors and projects that would protect the company from disruptors in the long run.

- Radical creativity and innovation are concepts from different fields: psychology and economics, respectively. While they both deal with new and transformative impacts, innovation, as discussed in business studies, is more focused on getting right the implementation of new business ideas and creating value.

Real-life activity

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Innovation, incremental innovation, disruptive innovation, radical innovation, radical creativity

References

- Christensen, C.M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston MA: Harvard Business School.

- Christensen, CM., Raynor, M.E., & McDonald, R. (2015). What is Disruptive Innovation?. Harvard Business Review. What Is Disruptive Innovation? (hbr.org).

- Dimitrov, D. (2014). Text-based indicators for architectural inventions derived from patent documents: the case of Apple’s iPad (Master’s thesis, University of Twente).

- Drucker, P. (2002). The Discipline of Innovation. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2002/08/the-discipline-of-innovation

- Hopp, C., Anthons, D., Kaminski, J. and Salge, T.O. (2018). What 40 Years of Research Reveal About the Differences between Disruptive and Radical Innovation. Harvard Business Review. What 40 Years of Research Reveals About the Difference Between Disruptive and Radical Innovation (hbr.org).

- Madjar, N., Greenberg, E., & Chen, Z. (2011). Factors for radical creativity, incremental creativity, and routine, noncreative performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022416

- Malik, M. A. R., Choi, J. N., & Butt, A. N. (2019). Distinct effects of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic rewards on radical and incremental creativity: The moderating role of goal orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(9-10), 1013-1026.

- Montoya, J. S., & Kita, T. (2017, June). Towards an improved theory of disruptive innovation: Evidence from the personal and mobile computing industries. In The Asian conference on the social sciences 2017: Official conference proceedings (pp. 125-144).

- Nordström, M. (2017). From incremental to radical innovation and corporate entrepreneurship.https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/29332

- Osterwalder, A. (2018). The Four KPIs to Track in Innovation Accounting. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/4-kpis-track-innovation-accounting-alexander-osterwalder/.

- Osterwalder, A., & Euchner, J. (2019). Business model innovation: An interview with Alex Osterwalder. Research-Technology Management, 62(4), 12-18.

- Schumpeter, J.A. (2010). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Tang, C., & Naumann, S. E. (2016). The impact of three kinds of identity on research and development employees’ incremental and radical creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 123-131.

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Gu, J., & Tse, H. H. (2022). Employee radical creativity: the roles of supervisor autonomy support and employee intrinsic work goal orientation. Innovation, 24(2), 272-289.

5. Impact

In this chapter, we explore how radical creativity impacts our lives, both individually and as a society, by bringing about significant changes for the better.

5.1 Systemic impact

You’ll learn about systemic impact and the key players involved in driving radically creative outcomes.

5.2 Paradigm shifting

You’ll explore how new assumptions and mindsets shape policies and societies, including examples of paradigm shifts in economic theories over time.

5.3 Future coming into being

You’ll understand personal and collective transformation as the foundation for creating a sustainable future, reflecting inner skills of creativity.

5.4 Changing the world for better

You’ll gain insights into various future scenarios while learning foresight methodologies and how creative practices support transformative futures.

5.5 Novelty and innovation

You’ll examine incremental, disruptive and radical innovation, understanding the distinctions between radical creativity and innovation. You’ll also learn how an interorganizational approach drives creativity.