What constitutes a paradigm shift? What cycles does a paradigm shift go through?

The concept of a paradigm shift was coined by Thomas Kuhn in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions to describe how scientific knowledge develops and changes over time. A paradigm is defined as the set of assumptions, values and beliefs, concepts and theories that shape a body of knowledge. A paradigm is shared by a group of experts within a domain at a certain point in time. Different domains, such as science, economy, society, technology and health, have all undergone paradigm shifts, changing what we know about the world and how we organize our societies.

Systems thinkers have an expanded understanding of paradigms and paradigm shifting. Donella Meadows20 sees paradigms, or mindsets, as the place from which a system—its goals, power structure, rules and culture—arises. The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions, constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.

Paradigms are harder to change than anything else about a system, but as Meadows argues, there’s nothing necessarily physical or expensive or even slow in the process of paradigm change. Even though societies resist challenges to their paradigm more than they resist anything else, a paradigm change can happen in a millisecond. All it takes is a new way of seeing.20

Quiz

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

How paradigms change

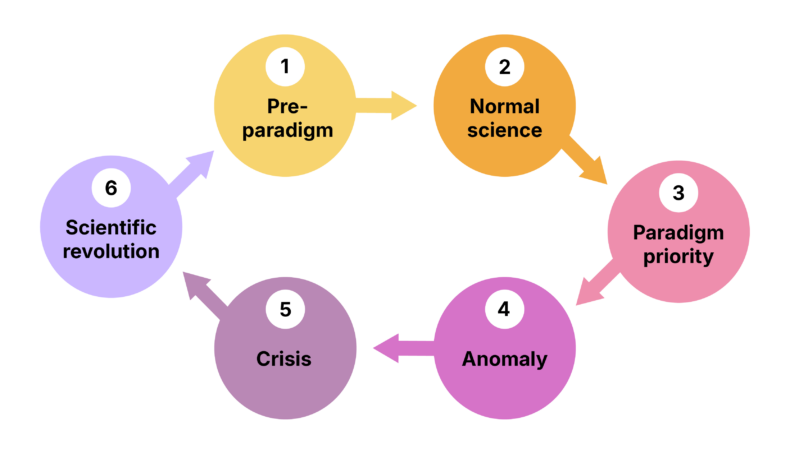

The phases of scientific revolutions

Kuhn15 describes the scientific paradigm shifts in six stages. Although Kuhn’s work focuses on science, a similar process can also happen when societal worldviews and values change in radical ways. Additionally, scientific paradigm changes often are central to society.

The six phases of paradigm change are:

1. Pre-paradigm

During this phase, the field is characterized by a lack of consensus on fundamental theories, methods, and standards of practice. Scientists in the field may adhere to various competing schools of thought or models to explain phenomena, leading to diverse and sometimes conflicting approaches.

2. Normal science

At this phase, one theory or model proves to be more successful than others in explaining phenomena, solving problems, and predicting outcomes. This success leads most of the scientific community to adopt this framework as the dominant paradigm, which then guides future research and knowledge creation.

3. Paradigm priority

Once a paradigm is established, it becomes the primary lens through which scientists view their field, influencing what questions are asked, how research is conducted, and how results are interpreted. The priority given to an existing paradigm means that scientific research is primarily conducted within its framework, often leading to incremental advancements rather than radical changes.

4. Anomaly

Over time, researchers encounter anomalies that cannot be explained by the existing paradigm. These anomalies are initially disregarded or seen as errors, but as they accumulate, they begin to challenge the validity of the current paradigm.

5. Crisis

When anomalies undermine the existing paradigm to a critical point, a crisis occurs, leading to a scientific revolution. This is a period of fundamental change in the scientific community’s view of the field, wherein new theories are proposed to better explain the data.

6. Scientific revolution

A paradigm shift happens when the community of experts adopts a new paradigm that better accounts for the anomalies. This new paradigm is not just an extension of the old one but a completely different worldview, which may be incompatible with the previous framework. This change in thinking redefines the strategies and what constitutes a valid idea worth investing time and resources.

Are we on the cusp of a new economic paradigm shift?

In their article Paradigm Shifts in Economic Theory and Policy, Laurie Laybourn-Langton and Michael Jacobs16 proposed that Western economics experienced two major paradigm shifts in the 20th century: first, from the laissez-faire paradigm to the post-war consensus and Keynesian economic policies, and later from the post-war consensus to neoliberalism.

The article highlighted similarities between the period of the time of writing the article, in many ways still continuing, and previous times of paradigm change. For instance, the financial crisis of 2007–2008 is likened to the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the oil price shocks of 1973, as all served as major disruptions to global markets. The economic instability has persisted, and Jacobs and Laybourn-Langton also connect this to the rise of populism.

The authors observed that there was a greater pluralism in academic economics in contemporary times compared to a generation ago, with many prominent economists criticizing dominant paradigms and policies. Furthermore, mainstream economic institutions such as the OECD, the World Bank, and the World Economic Forum had begun emphasizing the importance of sustainable and inclusive growth. Numerous think tanks, organizations, and student movements were also advocating for a fundamental transformation in economic policies. Time shows how this movement reacts to the changed geopolitical era of 2025 and onwards.

Case study

Amsterdam’s City Doughnut

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Changing societies

Pointing out the anomalies

So, how do you change whole societies? Meadows says that the key is the anomaly stage, as described by Kuhn.

‘In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep speaking louder and with assurance from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power,’ Meadows writes. She recommends not wasting time with reactionaries but rather to connect with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded.

Meadows also says that there is a leverage point even higher than changing a paradigm: ‘That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm is “true”, that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension.’20

Even though there is no certainty in any worldview, paradigms can be useful tools. Radical creatives can choose whatever paradigm will help achieve their purpose20. The humble state of ‘not-knowing’ is a point where radically new things start to happen.

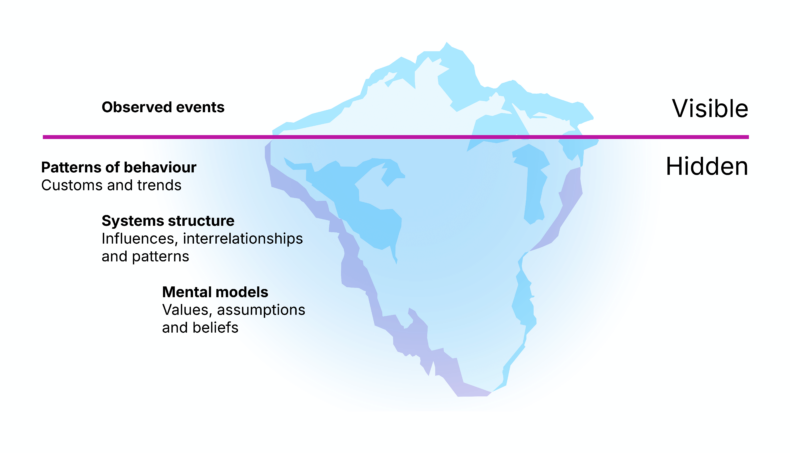

The iceberg

Everything that we cannot see but still need to change

Systems change and paradigm shifts require more than what we can see. The iceberg (see Figure 5.2.2.) is a visual tool to help us notice and work on the deeper structural blind spots and barriers to systems change. It helps us understand the underlying factors and less obvious dynamics and structures that influence human behavior and can cause problems.

Icebergs are famous for being much bigger underneath the water than what is seen over its surface. Instead of focusing on problems as something that needs to be quickly solved, it’s important to approach them as a symptom of something larger.

According to Otto Scharmer23, we live in a time of massive institutional failure, collectively creating results that nobody wants. The cause of this collective failure is that we are blind to the deeper dimension of transformational change. This blind spot exists not only at the institutional level but also in people’s everyday social interactions.

The most efficient factors that provide the deepest impact on system-level change tend to be invisible. So we really need to reach out and examine the mindsets, assumptions and values that influence us unconsciously. Questioning society-level issues means questioning things about ourselves. We need to look at ourselves—our inner world—preferably in dialogue with others.

Reflection

Your iceberg

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

From sustainability to regeneration

Shifting the paradigm for businesses—and for the whole society

Regeneration has become a new buzzword in the field of sustainable innovation. Businesses, entrepreneurs and other actors are increasingly noticing the value of going beyond sustainability and leaning into regeneration. This is seen as a paradigm shift that aims to create a deeper and wider impact and a fundamental shift in business practices.

A leading thinker in regenerative design, Daniel Christian Wahl26, sees this paradigm shift as a transition from doing things to nature to designing as nature, where people learn how to participate appropriately in the life-sustaining cycles of the biosphere.

A key difference between conventional sustainable development and emerging regenerative development is that the latter is based on a more holistic worldview that sees humans and economies as an intrinsic part of nature. Another key difference is that regenerative approaches start from potential instead of problems because problem-solving dictates a future based on past and present problems rather than being open to the entire range of possibilities. Regeneration is based on what is called ‘living systems thinking.’ It emphasizes the collective capacity to evolve toward increasing states of health and vitality over time. It focuses on learning how to think like natural systems so that people can shift their role as humans from a species that destabilizes and degrades to a species that revitalizes the living systems we inhabit11.

Thinking about place in concrete terms is often the best starting point for the relearning described above, because it’s the right scale for most people to think and care about. Place offers a communal ground for people across diverse ideological spectra. Place is what people share in common, and working at the scale of local communities, cities, and bioregions is where individual and collective behavior can make a difference.11

Real-life activity

Your doughnut economy

Well done! You have successfully completed this assignment.

Keywords

Paradigm shift, paradigm, pre-paradigm, normal science, priority of paradigms, anomalies, crisis, scientific revolution, mental shortcuts, human independence, economic growth, progress, creative impulses.

References

- Allgoewer, E. (2002). Underconsumption theories and Keynesian economics: Interpretations of the Great Depression. Forschungsgemeinschaft für Nationalökonomie an der Universität St. Gallen.

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for” mini-c” creativity. Psychology of aesthetics, creativity, and the arts, 1(2), 73.

- Bergson, H. (2003). Creative Evolution. Dover Publications Inc.

- Bertrand, R. (1997). Principles of Social Reconstruction. Routledge.

- Cole, H. L., & Ohanian, L. E. (1999). The Great Depression in the United States from a neoclassical perspective. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 23, 2-24.

- Dale, G. (2022). Rule of nature or rule of capital? Physiocracy, ecological economics, and ideology. In Economics and Climate Emergency (pp. 160-177). Routledge.

- Dolfsma, W., & Welch, P. J. (2009). Paradigms and novelty in economics: The history of economic thought as a source of enlightenment. American journal of Economics and Sociology, 68(5), 1085-1106.

- Florida, R., (2012). The Rise of the Creative Class. Basic Books.

- Glasner, D. (2023). Between Walras and Marshall: Menger’s Third Way. Available at SSRN 3964127.

- Glăveanu, V. P., & Kaufman, J. C. (2019). A historical perspective. In Kaufman, J.C. & Sternberg, R.J. (Eds), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed, pp 9-26).

- Gorissen, L., Bonaldi, K., Haerens, P. & Rato, L. (2024). Regenerative development and design. Commissioned by the Belgian Federal Public Service for Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment. https://fibsry.fi/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Leen-Gorissen_study_regnerativedevelopment.pdf

- Gudeman, S. F. (1980). Physiocracy: a natural economics. American Ethnologist, 7(2), 240-258.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99-127)

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of general psychology, 13(1), 1-12

- Kuhn, T. S., (2009). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The University of Chicago Press (3rd ed.)

- Laybourn-Langton, L., & Jacobs, M. (2018). Paradigm shifts in economic theory and policy. Intereconomics, 53(3), 113-118.

- Madjar, N., Greenberg, E., & Chen, Z. (2011). Factors for radical creativity, incremental creativity, and routine, noncreative performance. Journal of applied psychology, 96(4), 730.

- Magnusson, L. (2015). The political economy of mercantilism. Routledge.

- Mason, J.H., (2003). The Value of Creativity, The Origins and Emergence of a Modern Belief. Routledge.

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute. https://donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf

- Pincus, S. (2012). Rethinking mercantilism: political economy, the British empire, and the Atlantic world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The William and Mary Quarterly, 69(1), 3-34.

- Rashid, S. (1980). Economists, economic historians and mercantilism. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 28(1), 1-14.

- Scharmer, O. (2018). The essentials of Theory U: Core principles and applications. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Schumpeter, J. & Swedberg, R. (2021). The Theory of Economic Development. Routledge.

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (2003). The contributions of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. The Journal of Behavioral Finance, 4(2), 54-58.

- Wahl, D.C. (2016). Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press. Revised and updated 2022.

5. Impact

In this chapter, we explore how radical creativity impacts our lives, both individually and as a society, by bringing about significant changes for the better.

5.1 Systemic impact

You’ll learn about systemic impact and the key players involved in driving radically creative outcomes.

5.2 Paradigm shifting

You’ll explore how new assumptions and mindsets shape policies and societies, including examples of paradigm shifts in economic theories over time.

5.3 Future coming into being

You’ll understand personal and collective transformation as the foundation for creating a sustainable future, reflecting inner skills of creativity.

5.4 Changing the world for better

You’ll gain insights into various future scenarios while learning foresight methodologies and how creative practices support transformative futures.

5.5 Novelty and innovation

You’ll examine incremental, disruptive and radical innovation, understanding the distinctions between radical creativity and innovation. You’ll also learn how an interorganizational approach drives creativity.